We Should Not Accept Scientific Results That Have Not Been Repeated

The inconvenient truth is that scientists can achieve fame and advance their careers through accomplishments that do not prioritize the quality of their work.

Send us a link

The inconvenient truth is that scientists can achieve fame and advance their careers through accomplishments that do not prioritize the quality of their work.

New studies on the quality of published research shows we could be wasting billions of dollars a year on bad science, to the neglect of good science projects.

The pilot focuses on replicating studies that have a large impact on science, government policy or the public debate.

Suggestions of how to get started, in seeking to adopt a reproducible workflow for one's computational research.

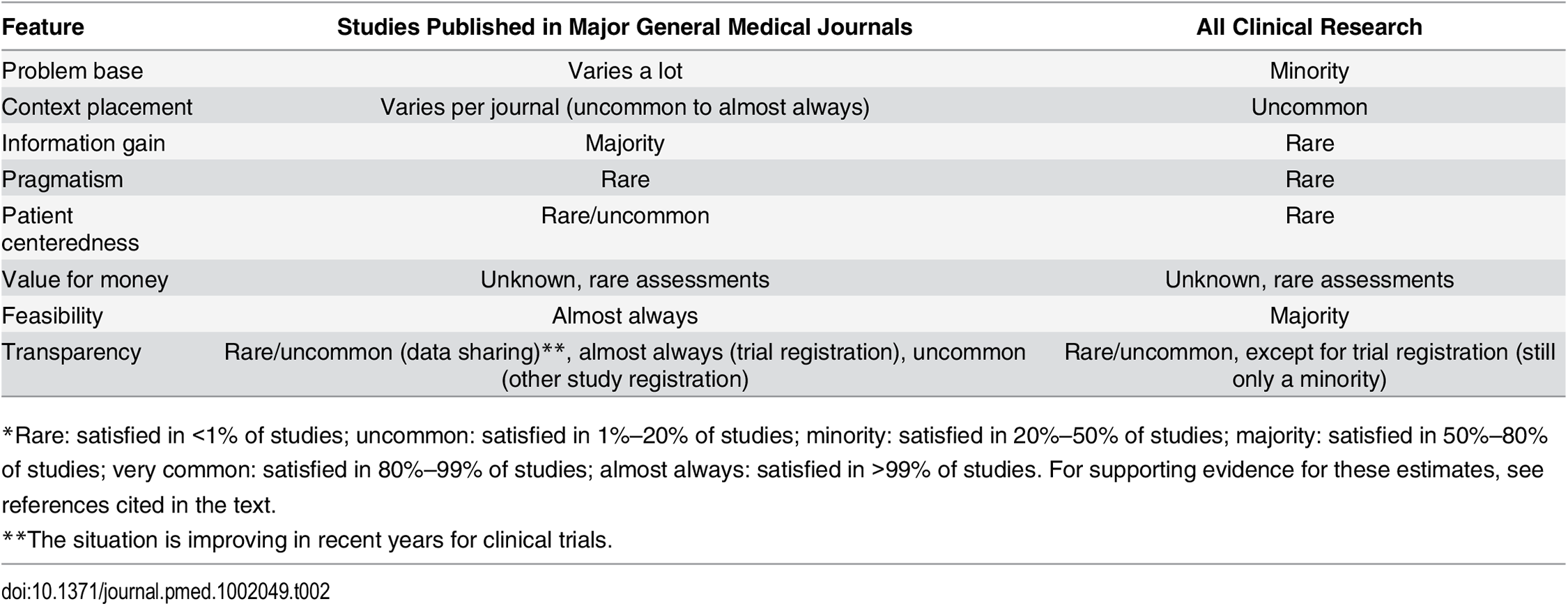

John Ioannidis argues that problem base, context placement, information gain, pragmatism, patient centeredness, value for money, feasibility, and transparency define useful clinical research. He suggests most clinical research is not useful and reform is overdue.

Software tools such as knitr and R Markdown allow the description and code of a statistical analysis to be combined into a single document, providing a pipeline from the raw data to the final results and figures. Outputs are updated by re-running the scripts using version-control tools such as Git and GitHub.

How can reproducibility be funded and enforced? One solution is to make it a part of the requirements to complete a PhD.

The former director of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences at the U.S. National Institutes of Health has a new job. On July 1st, biochemist Jeremy Berg will take the helm as the editor-in-chief of Science.

Researchers tease out different definitions of a crucial scientific term.

Many recent clinical and preclinical studies appear to be irreproducible; their results cannot be verified by outside researchers. This is problematic for not only scientific reasons but legal ones: patents grounded in irreproducible research appear to fail their constitutional bargain of property rights in exchange for working disclosures of inventions.

Jerome Ravetz has been one of the UK’s foremost philosophers of science for more than 50 years. Here, he reflects on the troubles facing contemporary science. He argues that the roots of science’s crisis have been ignored for too long. Quality control has failed to keep pace with the growth of science.

Science appears to be in something of an evolutionary cul-de-sac, mired in poor methodology and misguided objectives that have changed only for the worse.

Science has never been more powerful, but it is under attack.

The language and conceptual framework of “research reproducibility” are nonstandard and unsettled across the sciences. In this Perspective, we review an array of explicit and implicit definitions of reproducibility and related terminology, and discuss how to avoid potential misunderstandings when these terms are used as a surrogate for “truth.”

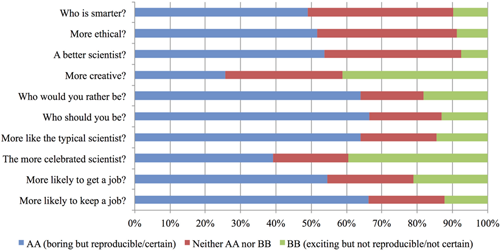

Placing trust in science can be easier when findings are confirmed, but a new survey finds that most scientists believe there is a reproducibility "crisis."

The current movement to replicate results is crippled by a lack of agreement about the very nature of the word “replication” and its synonyms.

Using the “#arseniclife” controversy as a case study, we examine the roles of blogs and Twitter in post-publication review.

There are better solutions to the “reproducibility crisis” in research

Survey sheds light on the ‘crisis’ rocking research.

Reputational assessments of scientists were based more on how they pursue knowledge and respond to replication evidence, not whether the initial results were true.

Science "deserves better than to be twisted out of proportion and turned into morning show gossip."

An opinon on the article "Merck Wants Its Money Back if University Research Is Wrong"

The current incentives structure — mostly based on publishing in prestigious journals — discourages sharing, replication, and, some argue, careful science.

Retractions are on the rise. But reams of flawed research papers persist in the scientific literature. Is it time to change the way papers are published?

A new analysis finds that 3.8 percent of scientific studies have images duplicated from another paper.

In 2012, network scientist and data theorist Samuel Arbesman published a disturbing thesis: What we think of as established knowledge decays over time.

If academic discoveries turn out to be wrong, one drug company wants its money back.

A discussion of the common underpinning problems with the scientific and data analytic practices and point to tools and behaviors that can be implemented to reduce the problems with published scientific results.

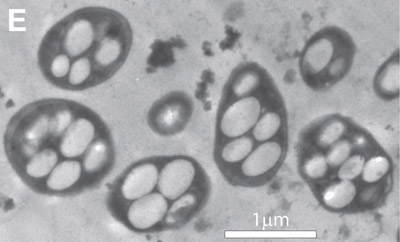

In response to rising concerns about irreproducible science and the lack of somewhere to openly discuss these issues, we recently launched the Preclinical Reproducibility and Robustness Channel.