Figuring out a Handshake

A solution to fix the replication crisis in science: why do scientists not simply sell what they learn from their research?

Send us a link

A solution to fix the replication crisis in science: why do scientists not simply sell what they learn from their research?

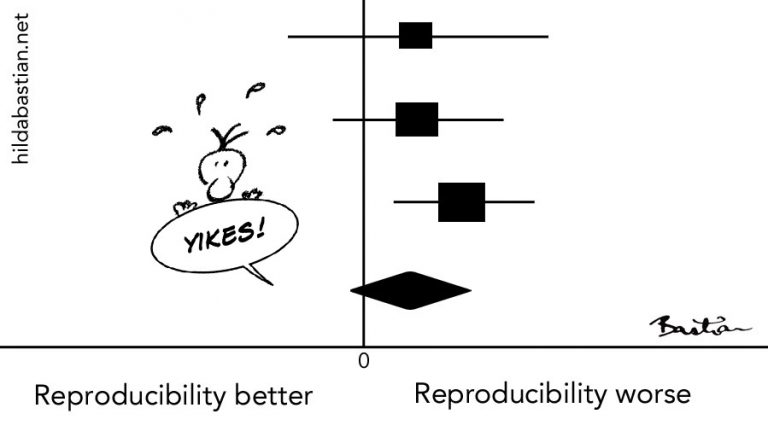

Llow replication success in psychology is realistic and worse performance may be expected for cognitive neuroscience.

In my scientific work I strive to be as open as possible. Unfortunately I work with data that I cannot de-identify well enough to share (aka weird sex diaries) and data that simply isn’t mine to share (aka the reproductive histories of all Swedish people since 1950)...

A growing chorus of experts says that scientific research is using too wide a net — and therefore publishing results that turn out to be false.

In this Viewpoint, Ioannidis discusses the problem of nonreproducibility in biomedical research and proposes implementing reproducibility assessments to improve research practices.

Two University of Washington professors are taking aim at BS in a provocatively named new course they hope to teach this spring.

A better understanding of uncertainty may help improve analysis and meta-analysis of data, and help scientists and the public have more realistic expectations of what scientific results imply.

Does that mean the original research was wrong? No. It means science is really, really hard.

Meet the former Enron trader and hedge fund founder who's on a quest to expose bad science.

Cut-throat atmosphere in world-class labs and conferences closer to House of Cards than Big Bang Theory, says Swiss academic

A project that tried to reproduce the results of 50 landmark papers turned into an arduous slog—and that’s a problem in itself.

Mixed results from cancer replications unsettle field.

In a sweeping manifesto, researchers from the U.S. and Europe have proposed some fixes for vetting published science. It might help science journalism, too.

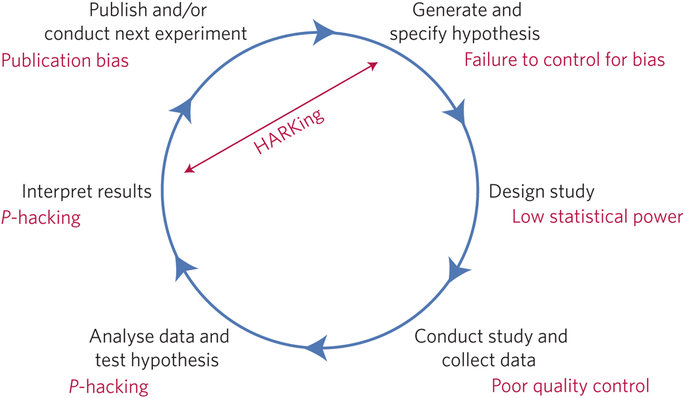

A series of measures improving research efficiency and robustness of scientific findings by directly targeting specific threats to reproducible science.

Fake news has been in the news a lot lately. Fake news proliferated wildly during the 2016 U.S. election, much of it completely fabricated, usually with an extreme partisan bias. Fake news is corrosive. It mis-informs the public, divides people against one another, leads to bad policy decisions, and can even induce people to take action against imaginary threats.

One of the watchwords of politics in 2016 was the epidemic of “fake news” — a catch-all term encompassing propaganda, misinformation, disinformation and hoaxing — impinging on the presidential campaign. But let’s not overlook its spread in the spheres of science and medicine.

Despite the typical stigma of retracting a scientific paper, Nathan Georgette is doing just fine — serving as a model to those many decades his senior.

Poor experimental design and statistical analysis could contribute to widespread problems in reproducing preclinical animal experiments.

It’s not a new story, although “the reproducibility crisis” may seem to be. For life sciences, I think it started in the late 1950s. A timeline.

Science fraud draws attention, but most scientists think it’s a far lesser threat to their field than the many times researchers cut corners.

Embargoes allow journals, universities, nonprofits, and corporations to decide what’s important — and when. That should be up to journalists.

Every scientist wants his or her paper to appear in Cell, Nature or Science. In today’s scientific world, being associated with such publications is synonymous with prestige and excellence, opening doors to top positions and coveted awards.

Experiments are invaluable and have, in the past, shown the consensus opinion of experts to be wrong. But those who fetishize this methodology can also impair progress toward the truth.

Making up names and CVs is one of the latest tricks to game scientific metrics.

And so, my fellow scientists: ask not what you can do for reproducibility; ask what reproducibility can do for you! Here, I present five reasons why working reproducibly pays off in the long run and is in the self-interest of every ambitious, career-oriented scientist.

A court case may define the limits of anonymous scientific criticism

Scientific research is being skewed by researchers and journals changing what they're looking for after the results of the study come in. But some people are finding ways to fight back against their own bias.

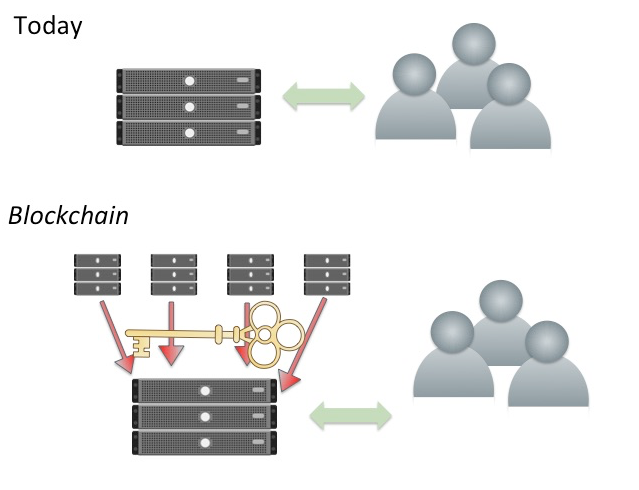

Blockchain could strengthen science’s verification process, helping to make more research results reproducible, true, and useful, due to its capacity to make digital goods immutable, transparent, and provable.

A computational guy’s take on the “reproducibility crisis”

Progress update from symposium sponsors: The Academy of Medical Sciences, the BBSRC, the MRC and Wellcome Trust.