Untangling Academic Publishing

A history of the relationship between commercial interests, academic prestige and the circulation of research.

Send us a link

A history of the relationship between commercial interests, academic prestige and the circulation of research.

Learned societies used to be seen as the guardians of academic prestige. They should act on that moral authority and reclaim their oversight of peer review, says Aileen Fyfe

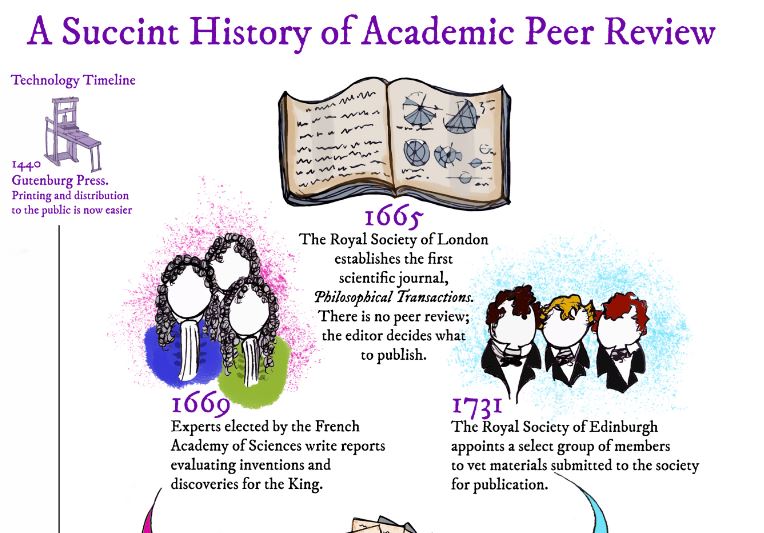

The imprimatur bestowed by peer review has a history that is both shorter and more complex than many scientists realize.

The report from SpotOn, 'What might peer review look like in 2030?' has now been published. This blog contains a section on the history of peer review from Frank Norman. Read the full report from SpotOn 2016 here.

Advances in science and public health policy have saved over 107 million lives in 25 years.

Many famous scientists have something in common—they didn’t work long hours.

Today's robots and artificial intelligence look very different from the androids conceived by Isaac Asimov.

The ability to participate in science has always been political. On International Women’s Day, scientists must decide how best to defend women’s rights

Research on collective recall takes on new importance in a post-fact world.

HBO has released the first teaser for its upcoming film The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. The story of Henrietta Lacks was documented in Rebecca Skloot’s 2010 book of the same title.

A man hunched over a microscope in Spain at the turn of the 20th century was making prescient hypotheses about how the brain works. Meet Santiago Ramón y Cajal, an artist, photographer, doctor, bodybuilder, scientist, chess player and publisher.

Humanity is going through unprecedented global change. The systems that arose to organize societies in the last 400 years are breaking down — and now is the time to envision what will come next.

“”Imagination is more important than knowledge.” - Albert Einstein

Moonshots, road maps, frameworks and more are proliferating, but few can agree on what these names even mean.

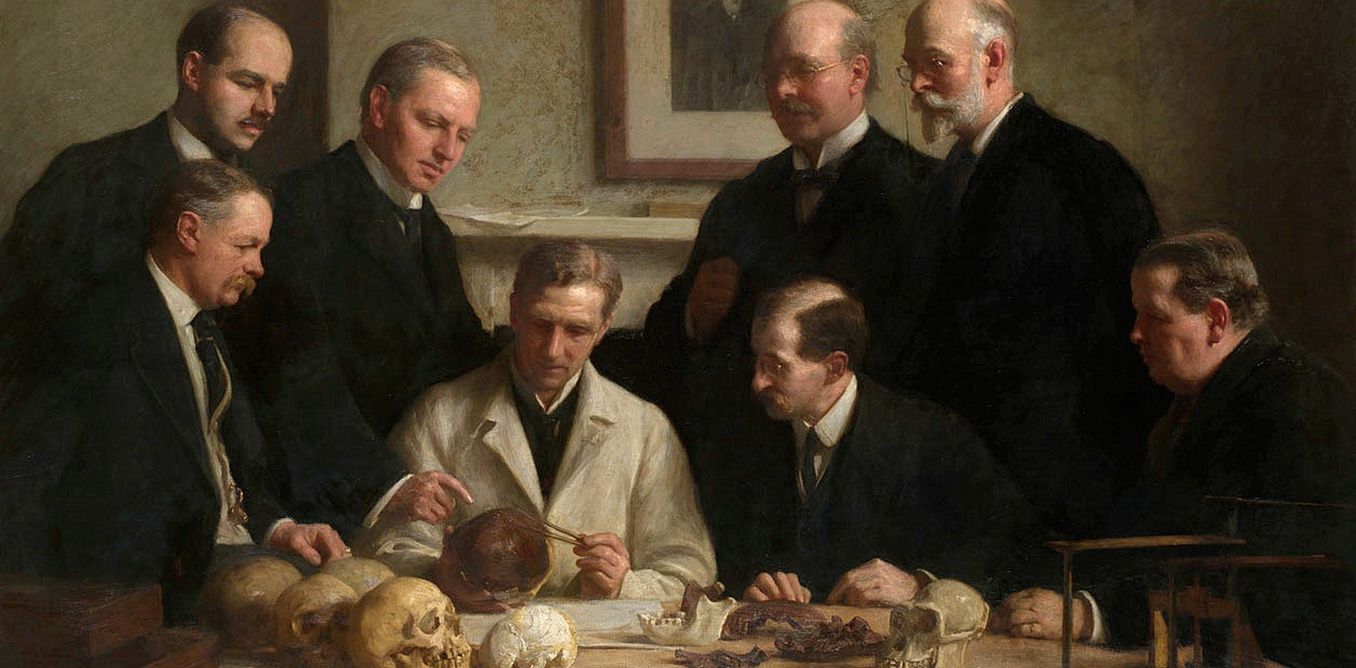

To claim credit for a discovery, we publish it in a peer-reviewed journal; to get a job in academia or money to run a lab, we present piles of these published papers to universities and funding agencies. Publishing is so embedded in the practice of science that whoever controls the journals controls access to the entire profession. It is, therefore, worth examining to whom we have entrusted the keys to the kingdom of science.

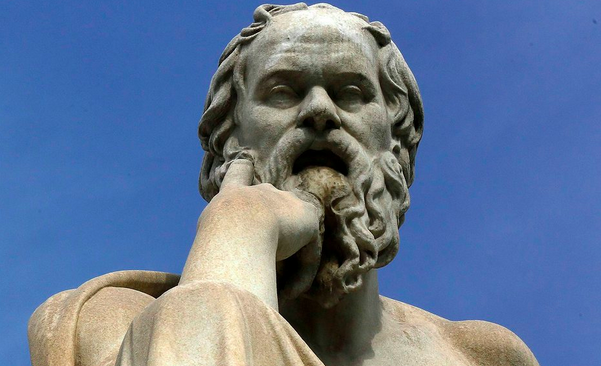

Philosophers could help policy makers to ask the right questions. But to give this practical help, academic philosophy must take lessons from open science.

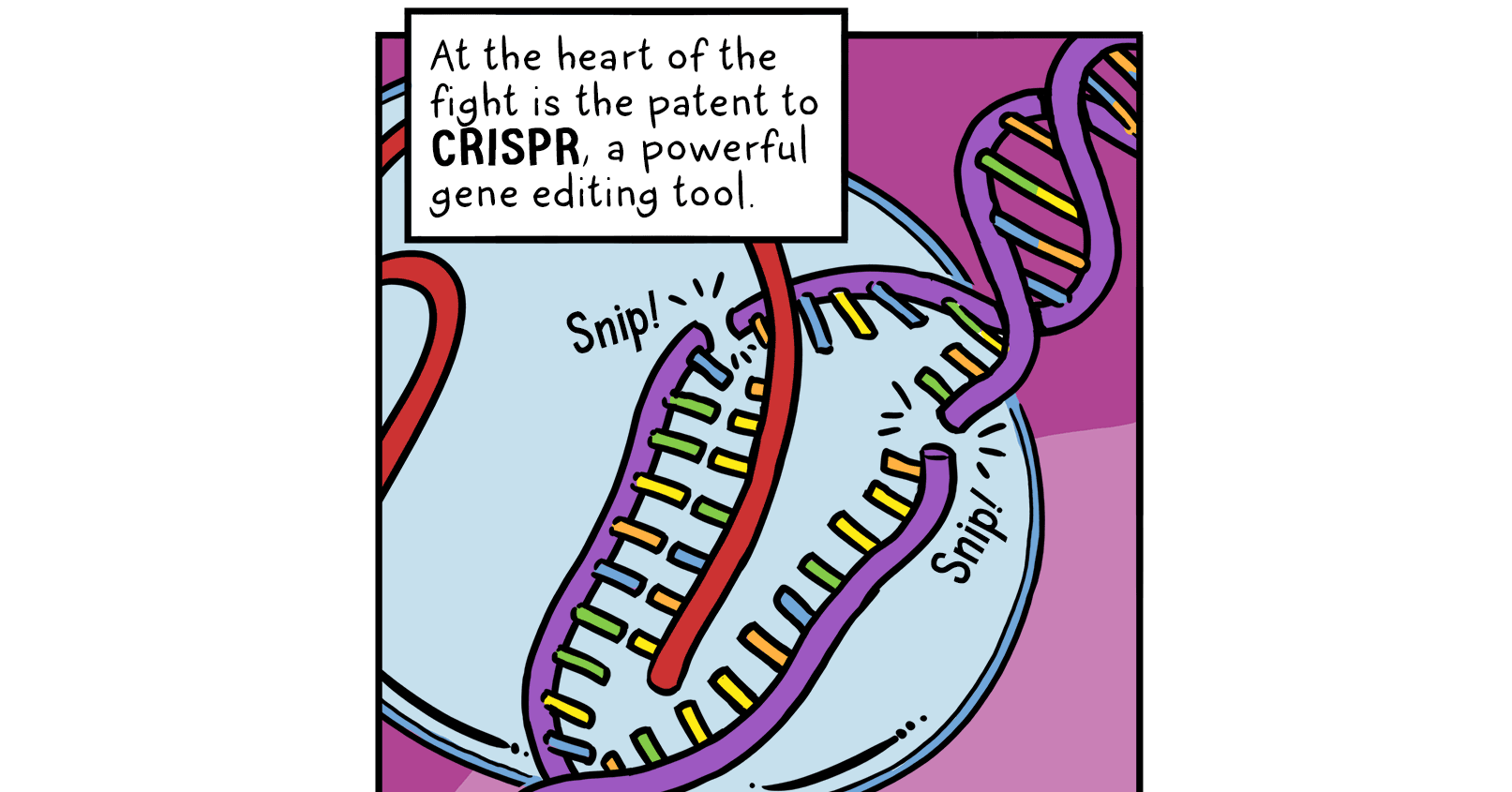

Who gets credit for the technology to cut-and-paste the human genome?

Although peer review is now a fundamental quality control measure implemented during the publishing process, the practice as we know it today is quite different from how it was envisioned...

A time traveler from 1915 arriving in 1965 would have been astonished by the scientific theories and engineering technologies invented during that half century. One can only speculate, but it seems likely that few of the major advances that emerged during those 50 years were even remotely foreseeable in 1915.

Barbara A. Spellman on the role of technological and demographic changes

Openly discussing the history of science, where is has gone wrong, and the incredible efforts individual scientists go to uncover fraud should inspire confidence in its self-correcting nature.